Cars and beyond 1926–1945

Bosch negotiated the rapids of economic crisis and National Socialist diktats with innovative strength and endurance till the second world war posed renewed immense challenges.

Diesel-injection pump — the second linchpin

Many years in the making, in 1927 an innovation came to fruition that would last right up to this day — the diesel-injection pump. This was the reaction of Bosch to the further development of diesel engines, which in contrast to gasoline engines required no magneto ignition. Initially used only in trucks, the first diesel-injection pump for cars went to market in 1936.

More strings to the bow — new lines of business

A major crisis in the German automotive industry led the automotive supplier Bosch to rethink its product portfolio from 1926 on. This inspired a combination of strategies that had proved successful in the past — the improvement of products and developing them to series production stage, as with power tools and thermotechnology, in tandem with entirely new endeavors, such as radio and television technology.

Power tools

Hair-trimming machines and hammer drills

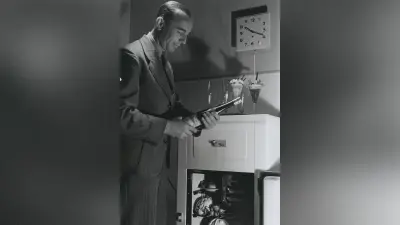

The Bosch engineer Hermann Steinhart encountered a device in his test workshop in 1927 that immediately fascinated him. The “Forfex” had an integrated motor in its handle. This opened up numerous new possibilities. Steinhart’s department initially brought the Forfex to the series production stage before developing the concept over the following years to create the first hammer drills. The team used the production facilities in the Bosch plants as a test facility.

Photo: A Bosch hammer drill in use (1936)

Allied excellence — production with a strong partner

Almost ten years after the end of the war, foreign sales had only climbed back up to 34 percent of the total. High transportation costs and customs barriers led Bosch to try out alternatives. In France, the United Kingdom, and Italy, the search commenced for partners for local production, and in Australia and Japan partner companies manufactured products under Bosch license. By 1932, foreign sales had risen to 55 percent.

FESE

Pioneering technology

Together with the Scottish pioneer of television, John Logie Baird, and the companies Zeiss Ikon and Loewe, Bosch founded Fernseh AG (FESE) in 1929. Years of research finally reaped initial major successes. FESE supplied the first electronic recording devices for the Olympic Games in Berlin in 1936 and, in that same year, presented the first “home television receivers.” During the war, FESE was commanded for military purposes to help develop a bomb with a built-in camera that could be controlled remotely via a television image. The end of the war halted the project during the test phase.

Photo: FESE home television receiver (1938)

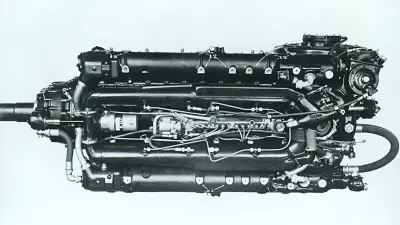

Gasoline injection for aircraft engines and television technology

When the National Socialists assumed power, this also presented Bosch with major challenges. The regime ordered research and development of gasoline-injection technology for aircraft engines and initiated the construction of new plants. Television technology in particular became the focus of military interest. The company’s foreign sales reached a low of nine percent in 1939.

Armaments and forced labor

With the start of the second world war, Bosch switched its operations to military production again. The military was so heavily motorized by that point that the company’s automotive activities were allowed to continue. As was the case throughout German industry, the associates called up for military action were replaced by forced laborers from the occupied territories, some of whom were forced to live and work in inhumane conditions.

Resistance and protecting the Jews

On the other hand, the Bosch company management actively supported resistance to the National Socialist regime. At its core was Carl Friedrich Goerdeler, who had been appointed as an advisor to the company. Persecuted Jews were also employed to save them from being deported to concentration camps, or were supported financially to assist their emigration.

The end

During the war, the Allies repeatedly bombed Bosch production facilities. Robert Bosch would not live to witness how parts of his factories were razed to the ground, as he died in 1942. He had left clear instructions to his successors on how to run the factory named after him.